In April, I had left my role as a compiler, VM, and game engine, engineer at Roblox. I had decided to not actively seek other jobs; instead I’ve been focusing a few new projects of my own: a C compiler, a break-through CPU emulator, and an IDE.

A C compiler, a CPU emulator, an IDE…

…are you getting it? They’re one project.

The two devices I have been most excited about in many years are iPad Pro and Vision Pro. However, the software support for writing systems software on these devices have historically been lack luster: many programming apps either only support traditional scripting languages (such as Lua, Python, or JavaScript), require an internet connection to phone home to a server that performs compilation and execution, or even opt to embed the entirety of Clang and LLVM in interpreter mode. The most competent attempt at meeting the needs and wants of engineers I have seen so far is Swift Playgrounds, with its ability to publish iPad apps directly from the app itself, and providing access to lower level frameworks. However, it still only supports compiling Swift.

So I have set out to build a suitable environment to write low-level systems programs directly on these platforms.

IDE

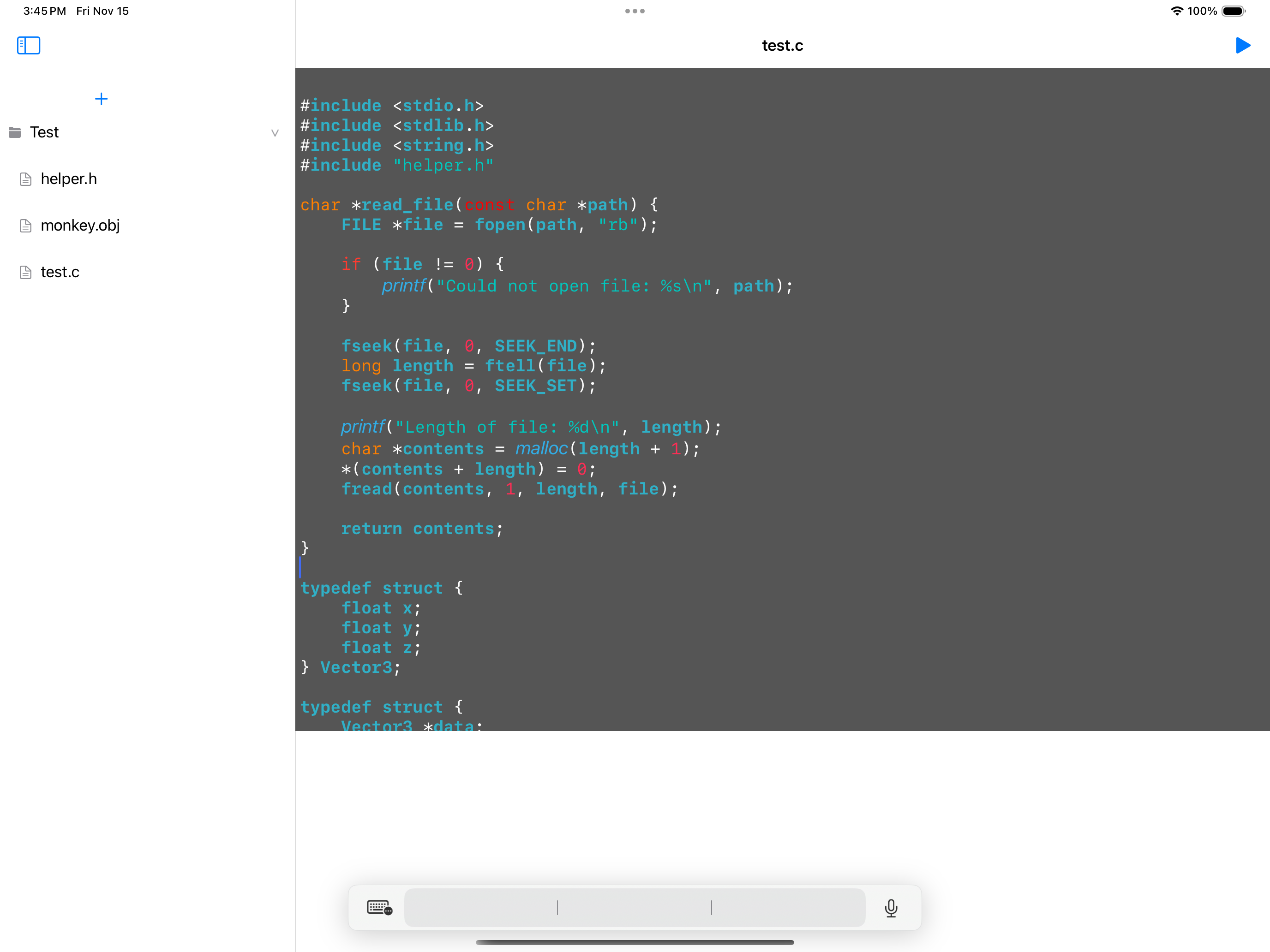

On the surface, the IDE app is fairly bare bones: there is a single “tab” for editing just one open file, a file tree, and an output window.

Errors

Code is being compiled and checked for errors on a continual basis. The IDE integrates deeply with the compiler to provide an error list window, and clicking on an error sets the editor’s selection to the token where the error was found. The editor also underlines all tokens where errors are currently being encountered.

Environment

What makes the IDE special is the runtime environment. Vertical integration with the CPU emulator enables user code to call special API functions in the IDE to do things such as rendering 3D graphics.

Sample code: https://gist.github.com/machinamentum/0c0c12c973915e9bbf45e16fd22eaf08

In the future, one can imagine even extending the editor via plugins writen in C via an API exposed in this way.

CPU Emulator

The intepreter engine emulates a RISC-style CPU with 16 integer registers, and 16 float registers.

Special built-in functions enable the emulated program to call standard C API’s, or call virtual machine functions that call into the app frontend. These mechanisms are not dlopen/dlsym wrappers, the runtime implements standard C API functionality, implementing checks and managing resources to prevent errors and leaks. printf, for example, is entirely implemented within the interpreter engine, including parsing the format string, and formatting the arguments (which are retrieved from VM registers); the app frontend need only provide a single putchar callback for the engine to report output characters to.

VM functions (those provided by the app frontend) are registed with the interpreter engine and called via a hash lookup of the name of the function. This is done in user code by calling a built-in function, call_vm_function, that takes the name of the VM function and performs a hash lookup to find the frontend callback to call.

[[builtinfn("call_vm_function")]] void call_vm_func(const char *name, ...);

int main () {

// Call the open_window VM function with the given title "My App Title"

call_vm_func("open_window", "My App Title");

}

The attribute [[vmfn("name_of_function_here")]] may be declared on a function declaration; this tells the code generator to call call_vm_function and to pass the given name as the first argument.

[[vmfn("open_window")]] void openWindow(const char *title);

int main () {

// Call the open_window VM function with the given title "My App Title"

openWindow("My App Title");

}

Note that in either case, the identifier of the declaration does not need to match the registered name of the VM function being called.

Memory is entirely sandboxed: the program sees “virtual addresses” that the emulator translates and bounds checks on loads and stores, catching memory access errors in the process. Under the hood, the interpreter manages regions of system memory with an assigned virtual address range, and access permissions. When the user program accesses memory, the virtual address, and size of the access, are checked against the ranges of the mananged memory regions; thus it is impossible for the user program to read/write memory outside of the sandbox.

C Compiler

The C compiler is entirely new; this is not another consumer of clang. Compilation speed is critical in this project; compilation, and execution, should always feel instantanous (even a simple Hello, World compiled with clang takes too long to compile and execute). As a poor example, a file containing 1 million printf calls takes 0.7 seconds (O2, 1.5ish in debug) to both compile and execute in this system, clang takes 7.6 seconds just to compile the file (M2 MB Air, plugged in to power).

The C compiler currently supports many foundational C language constructs including trickier-to-implement elements such as typedef and macros (with arguments). However, there is still a very long way to go to support compiling large and complex C programs.

On Clang and LLVM

Many projects opt to embed Clang to compile C code; sometimes utilizing Clang to parse C and translating the Clang AST into a format native to the project; sometimes embedding LLVM to compile and execute code. Why build a new C compiler? Weight, Velocity, and Fun.

For reference, the following LLVM build has been configued with cmake -S llvm -B build -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release -DLLVM_TARGETS_TO_BUILD="AArch64;ARM" -DLLVM_ENABLE_PROJECTS="clang". AFAICT, this is a best-case scenario for these tools.

Running ls -l in the LLVM 18 build directory in Release configuration, we can see that the clang binary is 110 megabytes, and the lli interpreter is 36 megabytes. It is unclear to me how much of the bloat can be stripped if one just wants the clang compiler and the LLVM interpreter in one binary, but I think it is safe to assume it would be on the order of 10s or 100s of megabytes. That’s far too large, by default.

machinamentum@Joshuas-MacBook-Air build % ls -l bin/clang-18 bin/lli

-rwxr-xr-x 1 machinamentum staff 110452360 May 20 01:06 bin/clang-18

-rwxr-xr-x 1 machinamentum staff 36207360 May 20 00:56 bin/lli

machinamentum@Joshuas-MacBook-Air build %

In comparison, the current size of the new compiler and interpreter is 206 kilobytes. That’s several orders of magnitude smaller, and I don’t expect the code size to increase by more than one order of magnitude by the time the project is in a shippable state.

machinamentum@Joshuas-MacBook-Air cvm % ls -l cvm

-rwxr-xr-x 1 machinamentum staff 206096 Nov 15 00:28 cvm

machinamentum@Joshuas-MacBook-Air cvm %

So, what is an acceptable size budget for our tools? How long should they take to download and install? How long should it take to build the tools from source? In an ideal world, the answer to these things would be small enough to download, build, and install instantaneously; however, a reasonable metric I now use is the time it takes to make a cup of coffee using a modern pod coffee system. Timing myself as I am writing this article, it takes just under 3 minutes to go to the kitchen, brew 3oz of coffee through an overpacked 3rd party pod (Nespresso Original Line style), and return to my desk. With an official pod that is packed properly, it would likely take closer to 2 minutes in total. The 2-3 minute range should be plenty of time for any toolchain to download+build+install on a modern computer. So how long does it take to build Clang + LLVM in the configuration mentioned above?

It takes 30 seconds just to configure the project:

cmake -S llvm -B build -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release 12.30s user 13.84s system 88% cpu 29.592 total

And another 16 minutes to compile the tools on a modern, fast machine (a M2 MacBook Air with 8GB of RAM, not a ridiculously powerful machine, but not an unreasonably low end machine either). This isn’t actually that bad; I’ve experienced many times in my life having to wait in excess of 30 minutes for an LLVM build.

cmake --build build -j8 7885.73s user 449.68s system 718% cpu 19:20.42 total

To build the new project, it takes just 3 tenths of a second.

machinamentum@Joshuas-MacBook-Air cvm % time ./build.sh

./build.sh 0.22s user 0.08s system 104% cpu 0.287 total

machinamentum@Joshuas-MacBook-Air cvm %